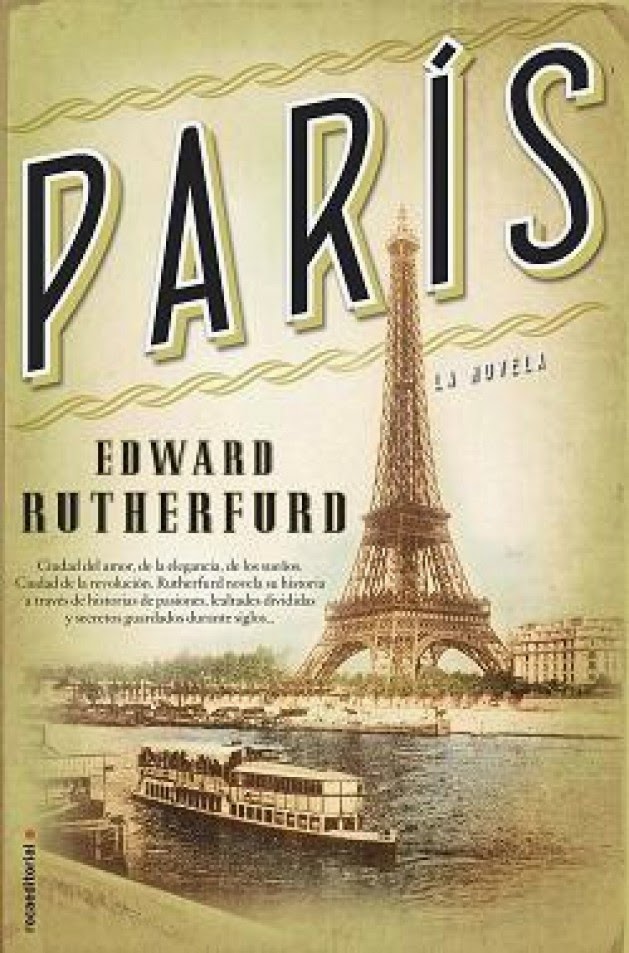

During December, though, I picked up Edward Rutherford's Paris. I have intended to read other books of his--London or Sarum. He had, after all, come highly recommended, and I always loved a good epic-style story spanning centuries in one place. This book fit the bill perfectly.

Once I got started, I wondered what had taken me so long. This book stays in Paris, following several families back and forth between the Middle Ages and post-World War II. Rutherford has an aristocratic family crossing paths with a family of wealthy merchants, a working class family, a Jewish family, and another family on the edge between legal and illegal activity. The storyline studies the roles of class and religion, always complicated, often changing.

Since I teach British literature, I feel relatively knowledgeable about that part of history, but this book helped me to fill in the blanks of French history--even European history in general. Instead of following a purely chronological order, Rutherford moves back and forth between centuries, with the family names as constant threads.

Having traveled to Paris and other parts of France with students twice several years ago, I especially loved revisiting places I had visited. The characters visit Sainte Chappelle, one of the loveliest spots in the city, a jewel box of a church, once reputed to display many holy relics. As they moved through Versailles, the Louvre, along the Conciergerie, along the Champs Elysees, I felt as if I were time traveling.

In one of my favorite story threads, one of the young men in the story works first on the Statue of Liberty, then on the building of the Eiffel Tower. Along the way, I learned so much history--without ever feeling as if I were being taken to high school. These stories were alive with the human beings that lived them--not just dates and place names. I had no idea, for example, that when Hitler came to Paris, he had wanted to go to the top of the tower, but the elevator cables had mysteriously been cut. Rutherford takes his poetic liberties here as he places fictional characters against his historical backdrop.

Reading Paris reminded me why I had once loved all of Michener's books and the historical novels by Follett. Now I need to take my copy of London off my shelf. As soon as I get through my Christmas gift books.