My June list of pleasure reading is usually much more extensive--but this is the first June in decades when I've been reading for classes I'm taking. My familiarity with comparative international education has been extensive, but doesn't make for scintillating book reviews.

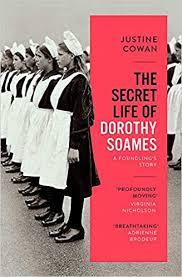

Justine Cowan's memoir The Secret Life of Dorothy Soames was a book club pick, one I hadn't even heard about before it made our list. I'm glad it did. While the author herself is certainly an important character in this story, the focus is on her mother, whom she only learned later in life lived her childhood with the name Dorothy Soames.

Cowan describes her own childhood living with a demanding, emotionally abusive, enigmatic mother. She grew up resenting the woman, confused by her father's complicity and protection of his wife, and not close to her own sister.

When her mother gave her a manuscript of her story, Cowan didn't read it--until after her mother's death. What she learned sent her to England to uncover her mother's secret past. She digs into the history of London's Foundling Hospital, where children--usually illegitimate--were raised in factory-like precision. Her mother had been left there as a baby after her mother, a single woman without the means to raise her daughter, applied for her acceptance. The philosophy of the founders and those who worked there was that illegitimate children bore the shame of their parents and should be trained for a life of service--as maids, soldiers, or sailors.

During the course of her investigation, she not only uncovered her mother story, but also learned about the interesting history of the institution. Quite surprising was the appearance of Handel (who played The Messiah there to one of his first appreciative audiences) and Charles Dickens, who wove details of orphaned and foundling children into his novels.

While Cowan learned that after WWII the grandmother she never knew had been allowed to take home young Dorothy, she was unable to find anything about what must have gone wrong. Those pages her mother intentionally omitted. If this had been a novel, the author could have tied up loose ends. Since it is based on historical events, though, readers can at least be hopeful that those who care for parentless children now have learned much about how to help them develop into healthy, successful adults.

Having read and enjoyed Daisy Jones and the Six, I was eager to read Taylor Jenkins Reid's new novel Malibu Rising. As I began, I was afraid it was going to be a tawdry tale of the lifestyle of Malibu celebrities, opening on the fateful night of an annual party in a magnificent home overlooking the Malibu beach. Instead, Reid weaves together the story of the children of Mick Riva, a Sinatra-like singer, and his wife June, whose family ran a local fish restaurant.